Eevery year the 193 member states of the United Nations General Assembly vote on dozens of resolutions, seriously shaking up the world. Last month, for example, they voted in favor of reducing threats to space travel, eradicating rural poverty and combating dust storms. The votes count for little. The resolutions of the meeting are not legally binding. Budgetary powers are small. And it has as many military divisions as the Pope.

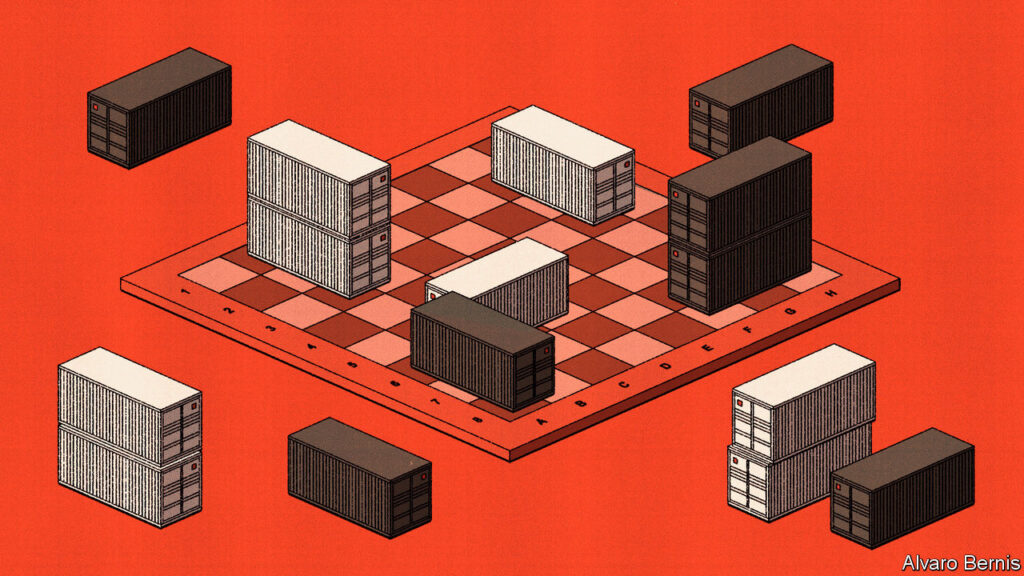

But for international relations scholars, these votes have long been a useful, quantitative measure of the geopolitical relationships between countries. More recently, economists have also turned to them. Due to the trade war between America and China, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the conflict in Gaza and the recent blockades in the Red Sea, geopolitics has become impossible for gloomy scientists to ignore. While their trade and investment models typically emphasize the economic size of countries and the geographical distance between them, they now also take into account ‘geopolitical distance’.

The latest such study was published this month by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think tank affiliated with the consultancy firm of the same name. By analyzing countries’ votes on 201 of the high-profile resolutions between 2005 and 2022, McKinsey was able to map countries’ geopolitical positions on a scale of zero to ten. America is at one end of the spectrum, labeled zero. On the other hand, Iran ranks ten. In between are countries such as Great Britain at 0.3, Brazil at 5 and China at 9.6.

The authors use this metric to provide a new perspective on each country’s trade. In addition to measuring the average geographic distance a country’s trade must travel, they also calculate the geopolitical distance it must travel. In a hypothetical world in which half of Iran’s trade was with America and half with Brazil, its trade would span a geopolitical distance of 7.5.

Their results are illuminating. European countries largely trade with each other. As a result, most of their business flows to their friends and neighbors. For Australia, however, things are a little less comfortable. It must trade with countries that are both geopolitically and geographically remote.

America is somewhere in between. Partly due to its continental size, it has few prosperous neighbors. Less than 5% of the global population GDP is generated by countries within 5,000 km of America, as McKinsey points out. The trade route travels an average of almost 7,200 km, compared to 6,600 km for Chinese trade and a global average of less than 5,200 km. Yet the world is not that far away on a diplomatic level. The geopolitical distance that US trade must travel is only slightly above the global average. It is much shorter than the diplomatic distances bridged by China. China’s trade spans a wider geopolitical divide than that of the other 150 countries in McKinsey’s data, with the exception of Nicaragua, which hates America but is doomed to do business with it.

The study finds some early evidence of ‘friendshoring’. Since 2017, America has managed to reduce the geopolitical distance its trade travels by 10%, on the McKinsey scale. For example, it has sharply restricted imports from China, although some of the goods it now buys from other countries, such as Vietnam, are full of Chinese parts and components. China has also reduced the geopolitical distance of its trade by 4%, although this required trading with countries that are geographically more distant.

Yet the report identifies several limits to this trend. Much of the trade that countries engage in with ideological rivals is trade out of necessity: alternative suppliers are not easy to find. McKinsey looks at what it calls “concentrated” products, where three or fewer countries account for the lion’s share of global exports. These types of products represent a disproportionate share of trade that extends over large geopolitical distances. For example, Australia dominates iron ore exports to China. Similarly, China dominates exports of batteries made from neodymium, a “rare earth metal.”

The effort to reduce geopolitical dangers could also increase other risks to the supply chain. Friendshoring will give countries a smaller number of trading partners, forcing them to put their eggs in fewer baskets. McKinsey calculates that if tariffs and other barriers were to reduce the geopolitical distance of global trade by about a quarter, import concentration would increase by an average of 13%.

For countries in the middle of the geopolitical spectrum, Friendshoring has little appeal. They cannot afford to limit their trade to other fence-sitters because their combined economic power is still too small. Countries that score between 2.5 and 7.5 on the McKinsey scale – a list that includes emerging economies such as Brazil, India and Mexico – account for only a fifth of global trade. To avoid falling through the cracks, they should try to trade across the geopolitical spectrum, just as they are doing now.

Friendshoring also has limits for China. There are simply not enough major economies in the geopolitical context to compensate for reduced trade with unfriendly Western trading partners. For China, ‘friendshoring’ is therefore more about replacing rivals and antagonists with more neutral parties in the non-aligned world, such as in Central Asia and the Middle East.

Check size

In studying how trade might twist along geopolitical lines, the McKinsey study assumes that the lines themselves remain fixed. But as the report openly admits, that may not be the case. The invasion of Ukraine and the conflict between Israel and Gaza are already creating new divisions and loyalties. It is conceivable that non-aligned countries will become politically closer to China, while China embraces them economically. By rejecting Chinese trade and investment, the West would certainly give China an additional incentive to curry favor with the rest of the world. After all, there are two ways to reduce the geopolitical distance of trade: trade more with friends or make more friends to trade with. ■

Read more from Free Exchange, our column on economics:

What economists have learned from the post-pandemic business cycle (Jan. 17)

Has Team Transitory really won the US inflation debate? (January 10)

Robert Solow was an intellectual giant (January 4)

For more expert analysis on the biggest stories in economics, finance and markets, sign up for Money Talks, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.